Manchu Archery: Heritage, Discipline, and Living Tradition

Manchu Archery, known internationally through the distinctive Manchu bow, represents one of the most enduring martial traditions of Northeast Asia. In China, this bow is called Qing Gong (清弓), named after the Qing Empire (1644–1912) by modern enthusiasts. The Great Qing was a conquest dynasty founded by the Manchu people of Northeast China. For the Manchu bannermen—famed for their strength, discipline, and battlefield prowess—the bow was far more than a weapon. It symbolized ethnic identity, social status, and a lifelong commitment to martial cultivation. European observers of the 19th century often referred to it simply as the “Chinese bow,” as it was the standard arm of the Qing military during conflicts with Western powers. Beyond the Manchu elite, the bow was also used by Han Chinese gentry preparing for the military examinations and by officers of the Green Standard Army, embedding it deeply into the broader fabric of Chinese martial culture.

In its native languages, however, the “Manchu bow” was simply a bow: gong (弓) in Chinese and “Beri” in Manchu. For clarity in international communication, the International Manchu Archery Association (IMNAA) uses the terms “Manchu Archery” and “Manchu Bow,” while acknowledging that this tradition is a shared cultural heritage. Over centuries, Manchu, Han, Mongol, and Hui practitioners all contributed to its refinement. Since the 1600s, the Manchu bow has been both a Qing bow and a Chinese bow, its practice interrupted only briefly by political upheavals in the mid‑20th century. Much like the Winchester 1873 rifle in American history, it served as the standard weapon of a vast, multiethnic empire. Today, archers around the world continue to train with the Manchu bow, drawn by its power, elegance, and cultural significance.

Manchu Archery—She (射) in Chinese and Gabtan in Manchu—was never merely a sport. It was a martial discipline intended to strengthen the body, refine technique, and cultivate the mind. Influential Qing archers such as Gu Hao (顾镐), Canging (常均) of the Yehenara clan, and Liu Qi (刘奇) wrote detailed commentaries on the philosophy and practice of archery. Their works, including Gu Hao’s Theory of Archery (She Shuo), The Theory of Shooting the Target (Gabtan‑i‑Jorin / Shedi Shuo), and Liu Qi’s Guide to Military Exam Archery (Liuqi Kechang Shefa Zhinanche), draw heavily from Confucian thought and the classical text The Meaning of Archery (射义) in the Book of Rites. They describe four inner cultivations essential to the archer’s development:

| English | Chinese | Manchurian | Definition by Gu Hao |

|---|---|---|---|

| Correct Mind | 正心 (Zheng Xin) | Gunin be unenggi oburengge | A mind free from evil and distraction. |

| Sincerity | 诚意 (Cheng Yi) | Mujilen be tob oburengge | The mind remains before the target, constantly examining intention and form. |

| Sustaining the Spirit | 存神 (Cun Shen) | Simen be teburengge | Move and stop with calmness, eliminating agitation. |

| Cultivation of Energy | 养气 (Yang Qi) | Sukdun be ujrennge | Forget gain and loss, showing neither joy nor anger. |

For these authors, the target symbolized one’s life goals, and archery became a metaphor for living with integrity, clarity, and purpose. Manchu Archery was therefore a path of self‑cultivation as much as a martial discipline.

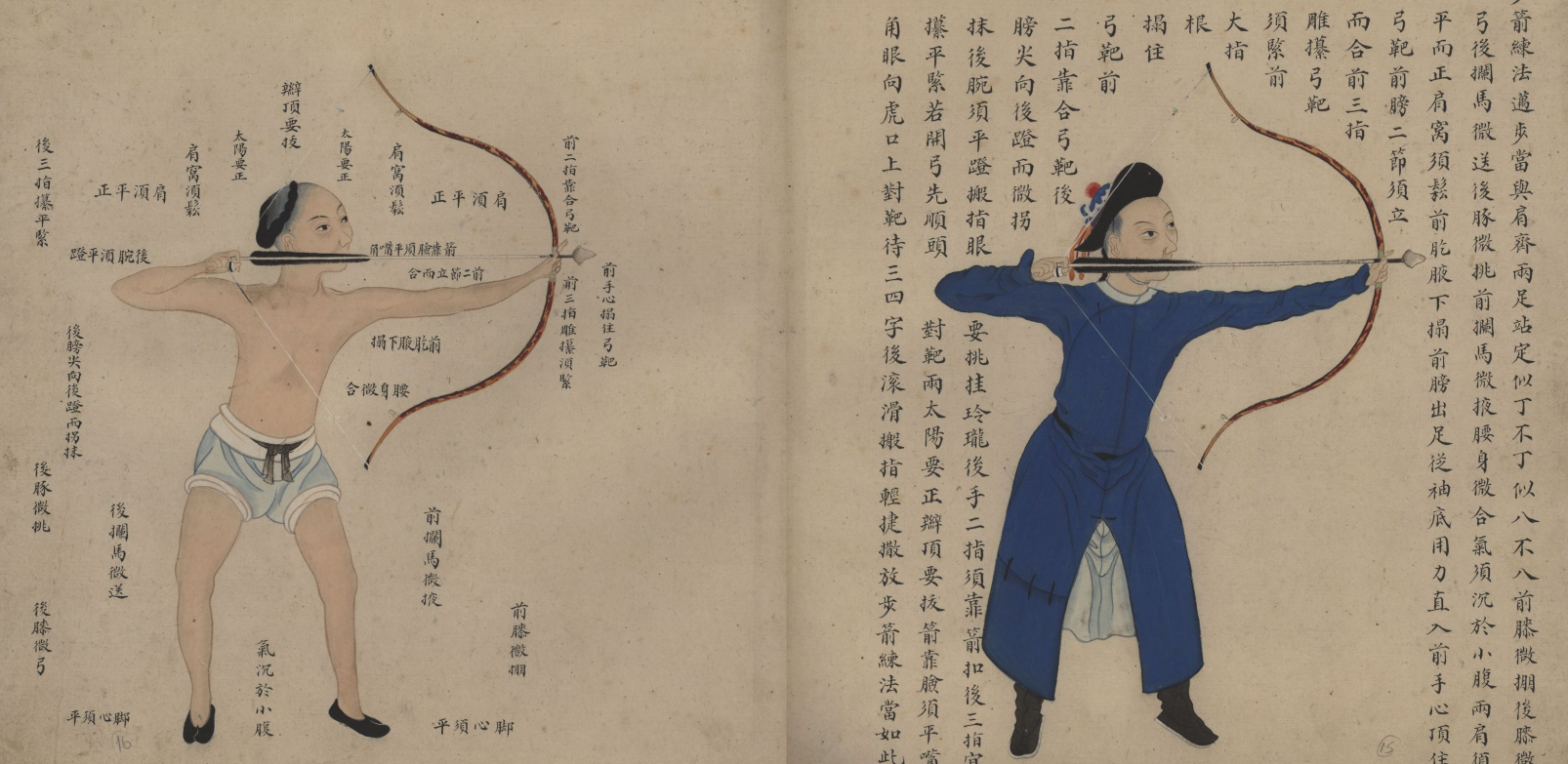

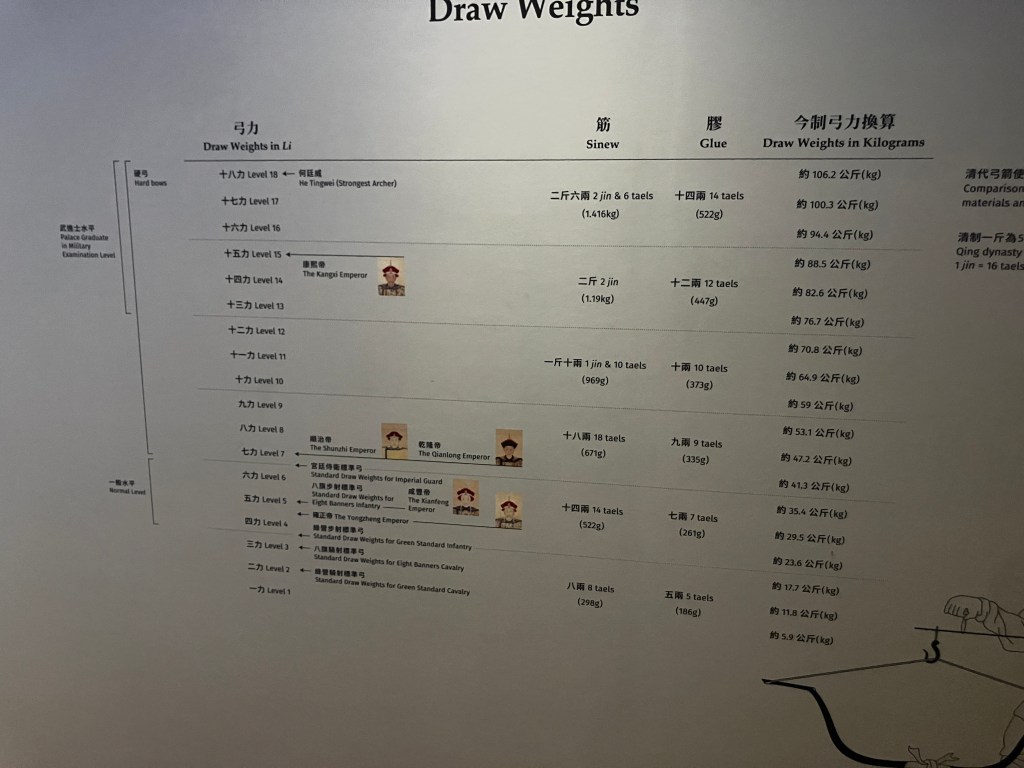

At the same time, Manchu Archery demanded formidable physical strength and technical precision. Manuals such as the Illustrated Handbook of Weaponry (兵器职掌图说), compiled by the Manchu official Niergingge of the Foimo clan, provide authoritative depictions of proper form on foot and on horseback. Historical records—including accounts by the French observer Étienne Zi and modern research on Qing military examinations—show that even in the late Qing period, examinees were required to draw heavy bows: at least 3 li (17.6 kg) on horseback and 5 li (29.3 kg) on foot, with strength tests reaching 8–12 li (46.9–70.3 kg). Targets ranged from 2.15 m (H) x 1.54 m to 1.69 m (H) x 0.77 m

in size and were placed at distances of 30, 50, or 80 bu (46–123 m). Surviving museum artifacts and imperial portraits confirm that Manchu bannermen, military gentry, and even emperors possessed the strength and refined technique required to shoot these powerful bows.

In keeping with this tradition, the International Manchu Archery Association recommends that modern practitioners train with two bows: a strength bow, representing the maximum draw weight one can handle with full form, and a shooting bow, approximately half that weight. This approach reflects historical ratios between mounted, foot, and strength‑test draw weights and ensures balanced development of power, accuracy, and endurance.

Members of the Canadian Chapter doing strength bow training

Manchu Archery today stands at the intersection of history, martial discipline, and personal cultivation. It invites practitioners to engage with a living heritage—one that challenges the body, steadies the mind, and connects modern archers with centuries of tradition. Through dedicated practice and cultural respect, the global community of Manchu archers helps ensure that the spirit of She and Gabtan continues to thrive.